The Aqaba-Amman desalination project is an innovative and sustainable plan to solve Jordan’s water scarcity

Dinner is in the oven and it’s bath time for the children. But the bath will have to wait – until the day after tomorrow, when the water comes back on. This is the reality in many parts of Jordan, where water is so scarce that it has to be rationed.

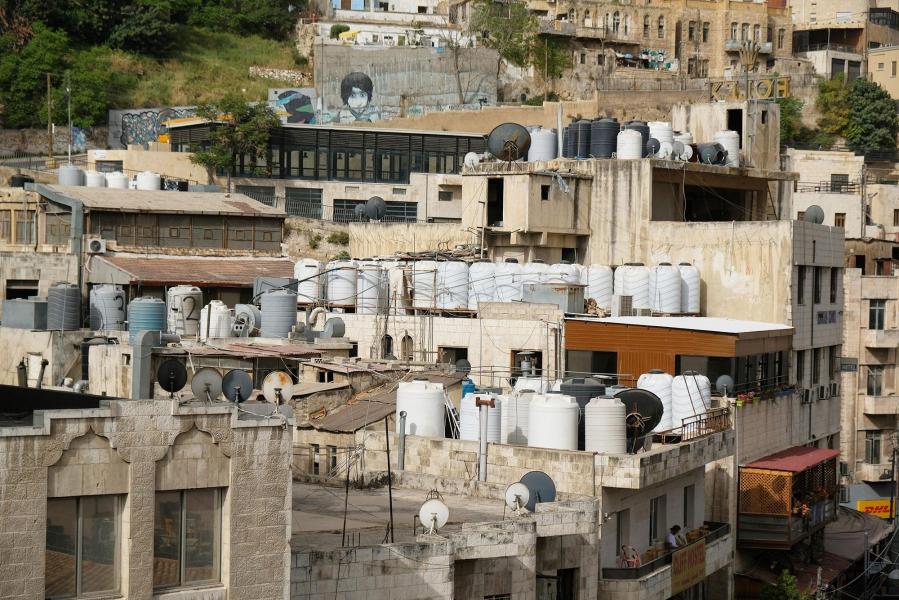

A country is considered to face water scarcity when it has less than 500m3 of water per person per year. Jordan has less than 100m3 of freshwater per person annually. Jordanians do not have regular access to water. Many keep water tanks on their roofs for when the mains supply runs out.

A new flagship project is expected to change all this by the end of 2028. The Aqaba-Amman Water Desalination and Conveyance Project will take water from the Red Sea at the Gulf of Aqaba in the south, desalinate it, and channel it 450 kilometres north to the capital Amman and its surrounding area, supplying a desperately needed 300 million cubic metres of water a year.

“Once this project is operational, there will be continuous water supply, 24/7, so people will no longer have to ration water,” says Souad Farsi, the European Investment Bank’s representative to Jordan. “This project is really transformational for people in Jordan.”

The mammoth infrastructure venture, the largest in the history of the country – and the region – is the fruit of cooperation between the Jordanian government, the European Investment Bank and Team Europe, as well as other international agencies and institutions. It is expected to cost €3 billion and to create 4 000 jobs during the construction phase.

The European Investment bank signed a €200 million loan with Jordan in December 2022, making it the first institution to commit its financing to the project. The procurement process is ongoing, and construction is expected to start in June 2024. The Jordanian government hopes to deliver desalinated water to the Amman area before the end of 2028.

Environmental and social impact assessment

The European Investment Bank’s involvement in the project started early on. Jordan had begun planning a new desalination plant, and in 2019 asked the EU bank to conduct an environmental and social impact assessment to help define long-term, best practice, environmentally sustainable solutions to the water shortage.

The Bank was just in the process of implementing its Economic Resilience Initiative, launched in 2016 to help countries in the region deal with the Syrian refugee crisis. As part of the initiative, the EIB’s Board approved a technical assistance budget of €90 million.

Technical assistance for the Aqaba-Amman project was approved under that budget to fund an environmental and social impact assessment, which was conducted by a consultant in cooperation with the Jordanian government and the US Agency for International Development, which has provided other technical studies for the project.

Jordanians keep water tanks on their roofs for times when no water is available

Causes of Jordan water scarcity

Jordan has always had very limited groundwater and surface water resources. The natural water scarcity is exacerbated by three main factors:

- Climate change has led to a significant reduction in rainfall and less refilling of aquifers

- Jordan’s population has grown rapidly over the past decade, to 11.1 million in 2022 from about 7.1 million in 2011, mainly due to refugee influx. It is expected to reach 16.8 million by 2040

- Non-revenue water, or water that does not reach its intended destination because of leaks, theft, or other reasons

Jordan aims to reduce non-revenue water from its current level of around 50% nationally to 25% of water supplied to urban systems by 2040. The Ministry of Water and Irrigation puts the investment needed to reach this objective at €1.7 billion over the next ten years.

Limiting environmental impact of desalination and pipeline

Desalinating water and transporting it across the country is an environmental challenge. The European Investment Bank’s environmental and social impact assessment of the project took two years, because extensive surveys had to be conducted to properly assess potential harm to the environment.

The consultant hired to perform the assessment “needed to hire boats and divers and to conduct surveys over several seasons,” says Harald Schölzel, lead water expert in the water security and resilience division of the European Investment Bank.

As a result, the project will:

- Take in seawater without destroying marine life, such as reef larvae. The consultants found that the larvae stay at a specific depth and can be avoided if the desalination plant draws in water at a different depth, at a limited velocity, and over a large surface

- Eject none of the chemicals used in the desalination process back into the sea. For this, a wastewater treatment plant will be incorporated into the desalination plant

- Safely dispose of leftover brine, which has double the salt concentration of seawater. A simulation showed that if the brine is shot out into the sea with hoses at a high velocity over a large area, the salt concentration at 20 metres away is just 1% above the normal level, and beyond 50 to 100 metres it is undetectable

- Power the plant and pump water over 400km while keeping carbon emissions low. Emissions were capped at the equivalent of 3.2 kg of CO2 per cubic metre of desalinated water

- Build photovoltaic fields without damaging nature reserves or disrupting the flight path of the 500 million birds that migrate through Jordan every year.

“Being the climate bank, we discussed with the government the optimal solutions for the power supply to the project, since Jordan has ample renewable energy resources, especially for solar power,” says Alexander Abdel Gawad, a loan officer with EIB Global, the European Investment Bank’s development arm.

Financing the Aqaba-Amman desalination project

After the European Investment Bank helped Jordan define the project’s technical specifications, the discussion turned to financing. The project’s cost was estimated at around €3 billion, and the EU bank brought in other partners to raise the funds.

“We wanted to be involved in financing the implementation, because we knew that our involvement could attract other financiers,” says Abdel Gawad.

The Bank turned to Team Europe, which includes the European Union, its Member States and their agencies.

Grants and loans worth $1.83 billion were pledged for the project at an international conference in Amman in March 2022. Since then, additional pledges have pushed the total to $2.35 billion, according to Jordan’s Ministry of Water and Irrigation.