Jordan’s first big wind farm sets the Arab country on the road to renewable energy success

The desert road follows the route of the ancient spice caravans that converged on the Nabatean city of Petra and of the Bedouin tribesmen who rode with Lawrence of Arabia to capture the southern port of Aqaba in World War I. The mountains rise from the plain, rugged and rose-red, before they dive to the Dead Sea. Amid all this history and natural beauty, Jordan Wind Project Company has created a new feature on the landscape that could have an important role in the country’s future.

Spinning in the winds that sweep across the desert flats, the 55-metre-blades of Jordan Wind Project’s 94-metre-high turbine towers flash against the sun. “They are very beautiful structures,” says Samer Judeh, the company’s 49-year-old chairman.

The Tafila Wind Farm, which takes its name from the local governorate, started commercial operations on 16 September, after 21 months of construction and testing. In the shadow of conflict or civil unrest in neighbouring Syria, Iraq and Egypt, the USD$287 million project defied regional instability just as surely as its towers stand unbent by the desert gusts.

The project’s financial backers, which include the European Union’s bank, the European Investment Bank, believe Tafila’s towers are the sentinels of a new industry that will transform the country’s economy. Jordan aims for renewable energy to contribute 10 percent of its needs by 2020. That’s vital to a country whose energy costs eat up 20 percent of its gross domestic product.

A changeable backdrop

When Jordan Wind Project’s sponsors first considered renewable energy in Jordan in 2011, the picture was very different. The kingdom hadn’t finalized legislation to support renewable energy projects, and it also was short of natural resources. Unlike most of its Arab neighbours, Jordan has no oil reserves and very little natural gas. Traditionally its only major resources were deposits of potash and phosphates mined for use in fertilizers.

Still the company went ahead, backed by its team of sponsors:

- Inframed Infrastructure, a Paris-based fund that invests in the Mediterranean region

- Masdar Power, an Abu Dhabi developer and owner of renewable energy projects

- EP Global Energy, a renewable energy developer and owner based in Cyprus

The development team found a perfect spot for the wind farm in Tafila, the least populous of Jordan’s government districts and the centre of the biblical kingdom of Edom. East of the tiny village of Gharandil, the company leased land that was previously used very sparsely for grazing goats. The site had no permanent dwellings, little vegetation and no water sources, so people and livestock were unlikely to be much disturbed by development.

But the backdrop got more unstable as the project went on.

- In 2011, Syria descended into civil war. Jordan found itself host to as many as 750,000 Syrians

- In the turmoil after the overthrow of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak the same year, the gas pipeline through the Sinai Desert to Israel and Jordan was sabotaged by local Bedouin. The gas shutdown hit Jordan’s National Electric Power Company, which uses Egyptian gas to produce 58 percent of the kingdom’s power

- The gas shutdown pushed up electricity prices, sparking riots across Jordan in 2012. Even after Egypt put the pipeline back into operation, gas was often unavailable because of supply shortages or sabotage attacks

Who needs oil?

Even so, the wind farm project excited officials at the European Investment Bank. It fitted EIB’s strategy to make a quarter of its loans to projects aimed at mitigating or adapting to climate change effects. Wind power replaces sources of energy that emit greenhouse gases.

The EIB insisted that the company perform an in-depth study of the wind farm’s environmental impact. One night at 1 a.m. a Jordan Wind Project negotiator telephoned Cathérine Barberis, who leads Jordan loan operations for the EIB in Luxembourg, concerned that such stringent preparations would delay the project. “It’s more work,” Barberis told her. “But it’ll be worth it.”

In return the EIB agreed to loan Tafila up to $72 million.

The project was a first for Jordan’s government and business community, and EIB officials had to push through uncharted territory too. “Nobody was in their comfort zone,” Barberis says. “We always had to think of ways to be creative.”

Still the EIB’s requirements made the project more transparent. The bank’s presence, along with the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation which also had a leading role in the project, encouraged other investors to join. Tafila is supported by loans from:

- EIB (26 percent)

- The International Finance Corp

- FMO, the Dutch development bank

- Europe Arab Bank

- OPEC Fund for International Development

- EKF, the Danish export agency, which provided a loan guarantee

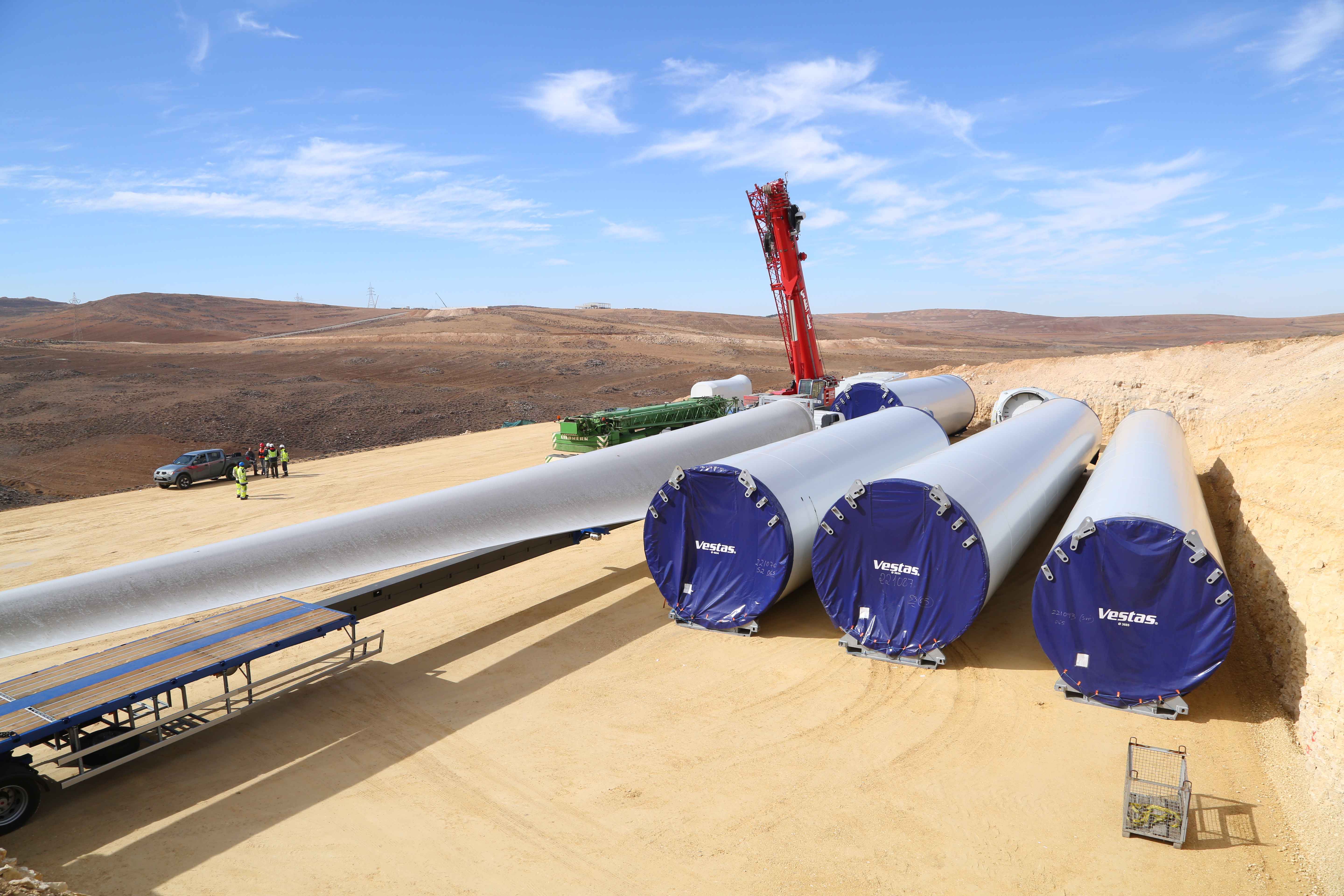

It was a Danish company, Vestas Wind Systems, which was selected to provide Tafila’s turbines. The Aarhus-based firm’s V112 turbines now stand sharp against the desert skies.

Migrant birds and local workers

The project’s main environmental issue was the flight paths of migratory birds. Every year a half billion birds pass over Jordan and neighboring countries on their seasonal migration between Africa and Europe. Jordan Wind Project partnered with the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature to assess the risks and to mitigate them so they complied with the EIB’s environmental requirements.

In the end the wind farm buried its electrical cables to prevent electrocuting the birds and decided to shut down the turbines when large migratory flocks approach. Jordan Wind Project staff also agreed to keep a special look out for griffon vultures, which lurk around the area seeking carrion.

EIB officials say they were impressed by the company’s insistence on working closely with the local Bedouin communities around Tafila. This helped align the project with the bank’s social requirements. Jordan Wind Project leased the land for the wind farm from locals and hired 85 percent of its workers from among them. Many of the vehicles and plant used on the project were leased from local people too. “They were very culturally sensitive,” says Barberis.

Next step: more wind, and solar

Now that Tafila is running, its 38 turbines will produce 400 gigawatt hours per year. That’s enough to power more than 83,000 of Jordan’s 1.2 million households. Thankful to be less dependent on imported electricity and Egyptian gas pipeline, National Electric Power (NEPCO) signed a 20-year deal to take all of Tafila’s production.

The project also sets up Jordan to develop an entire renewable energy sector. Working with the EIB and other lenders, the country’s government ministries created the administrative processes to examine and approve new projects. It also built the customs capacity to handle the massive machinery and parts used during construction of the towers in the desert.

The EIB is deeply involved in that future growth already. The bank expects soon to sign a USD$80 million deal with the Jordanian government to finance the infrastructure that connects future renewable energy projects to the country’s electrical grid, a project known as the “NEPCO Green Corridor.”

Judeh says there are 14 “bankable wind-speed locations” in Jordan’s deserts. With the EIB also exploring possibilities for new solar energy projects in Jordan, the tall outline of Tafila’s turbines looks like being only the first landmark of a new industry in the desert kingdom.