In early September, a 6.8-magnitude earthquake shook the Alhaouz region in the heart of Morocco, destroying 50 000 homes and severely damaging 1 000 schools, many of which had to be demolished. Teachers and students in rural areas most affected by the disaster lost their homes and were forced to sleep in the highly damaged school buildings, which were already seriously rundown even before the earthquake hit.

While Morocco spends about 5% of its gross domestic product on education, current resources aren’t enough to maintain, upgrade and expand the network of 8 022 primary schools, particularly in rural areas. These old buildings haven’t been renewed since they were built in the 1970s and 1980s, and they offer poor sanitary conditions for students and teachers, who have to walk great distances to learn and teach.

Morocco was already planning to build new infrastructure as part of a national effort to improve education in remote areas, like the Atlas Mountains, which trail the rest of the country in academic performance. (Only 44% of girls in rural areas attend lower secondary schools, compared with 82% in urban areas.) After the earthquake, the Ministry of Education is speeding up applications for building permits, so that reconstruction can begin by end of 2023.

“This project is a game-changer for education in Morocco,” says Didier Bosman, a senior architect who’s working on the European Investment Bank’s financing for the project. “It’s a top priority for the Moroccan Ministry of Education, to close the gap between urban and rural areas.”

The European Investment Bank loaned €102.5 million to Morocco to build 150 community schools (pre-primary and primary schools), and to provide necessary infrastructure such as school equipment, boarding facilities and transport. All the resources will now be shifted to areas hit hardest by the earthquake.

In October, the European Investment Bank pledged €1 billion over the next three years to Morocco's post-earthquake reconstruction programme.

To help plan the investments, Morocco also received an additional grant of €650 000 under the EIB’s Economic Resilience Initiative, a fund which supports resilient and inclusive growth in Europe's Southern Neighbourhood and the Western Balkans. That will pay for technical assistance in planning the project, which includes an in-depth study of the needs and challenges of rural schools.

The study will serve as a blueprint for future education projects in the country.

Educational challenges

Only 27% of Moroccan 15-year-olds attain minimum proficiency in reading, against an average of 77%, according to the latest data from the Programme for International Student Assessment by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. High drop-out rates in the early school years mean that only two-thirds of young people finish lower secondary education.

At the same time, one of the main obstacles to gender equality is girls dropping out of school, which weighs on their job prospects.

“Education in Morocco is mandatory until age 15, and it’s free,” says Bosman. “The issue is that many children fail to attend, girls in particular. Less than 60% of children finish middle school in urban areas, and in rural regions, they don’t even enrol as they need to help their families.”

The European Commission is also providing extra support through bilateral programs in education in Morocco.

Rundown rural schools

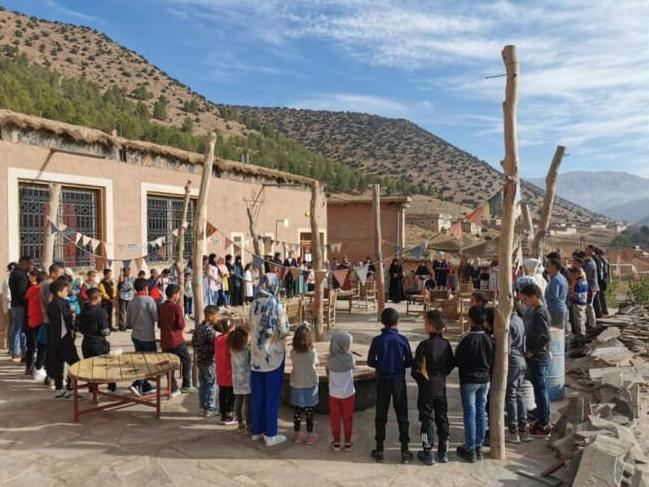

Rural primary schools in Morocco are considered satellite schools, learning spaces that are physically distant from the original campus and usually smaller. Some of these learning spaces are run without a headmaster.

The approach brings schools closer to the inhabitants of rural and extremely remote regions, but the infrastructure is rudimentary, with simple concrete buildings. Schools can overflow with 800 students whereas they were designed for a maximum of a hundred.

Teachers and students often live on site, particularly since some children travel long distances to get to school. Living conditions are poor, without electricity or functioning bathrooms. This lack of infrastructure poses problems for adolescent girls, many of whom drop out of school when they start menstruating or when they start secondary school a long way from home.