Why small innovative companies in Europe are less likely to create growth – and what we can do about it

Christoph Weiss, economist at the European Investment Bank

We’ve all read the stories about a couple of friends starting a business in a garage. The story usually goes like this: The friends launch an innovative product or service, and soon their company is providing thousands of jobs and they are billionaires.

Well, in Europe, innovators are mostly older and larger firms. The fact that older and larger firms are innovating is obviously not bad. But it begs the question as to what is holding back small, young firms. Oftentimes young small firms do not engage in any type of R&D or innovation at all.

The results of the EIB Investment Survey (2016) confirms this. The survey covers thousands of companies across different sectors and all 28 countries of the EU. We used the results last year to publish a paper “Young SMEs: Driving Innovation in Europe?”, together with colleagues from KU Leuven University and the European Central Bank.

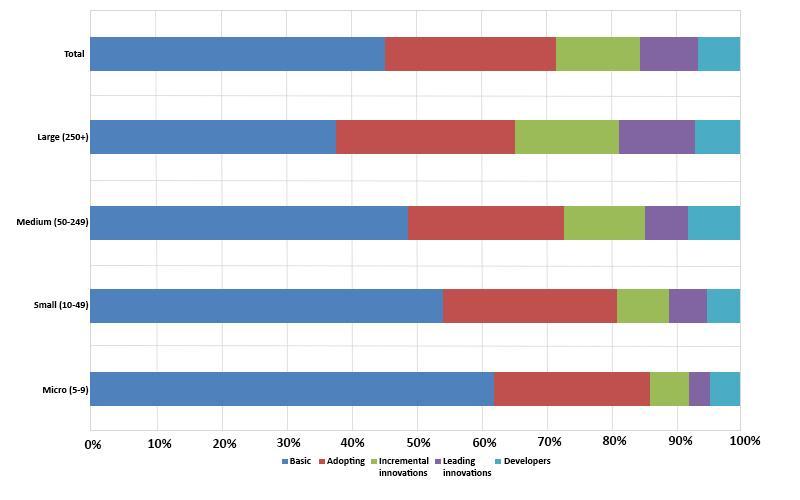

In our study, we split companies into five groups:

- Basic firms (52%) – no significant R&D investments (less than 0.1% of turnover), and no innovation

- Adopters (26%) – no significant R&D investments (less than 0.1% of turnover), but introduce existing innovation

- Developers (5%) – firms that invest in R&D, but do not introduce innovation (yet)

- Incremental innovators (10%) – firms that invest in R&D, and also introduce innovation that is new in the country or to the firm, but not to the global market

- Leading innovators (7%) – firms that invest in R&D and introduce completely new products/processes

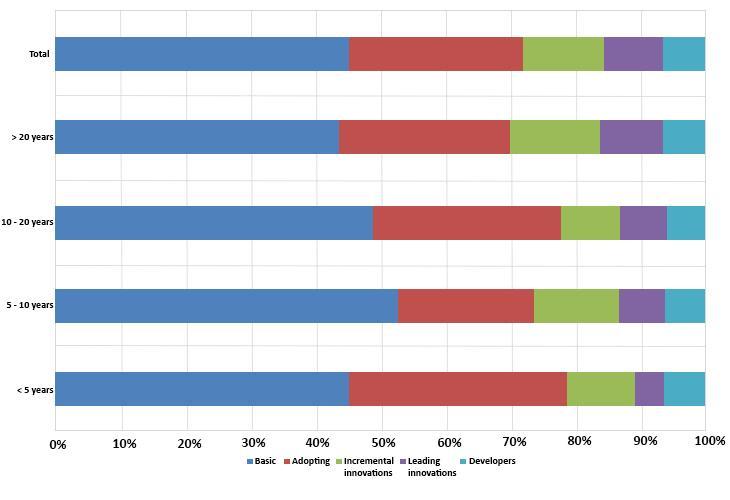

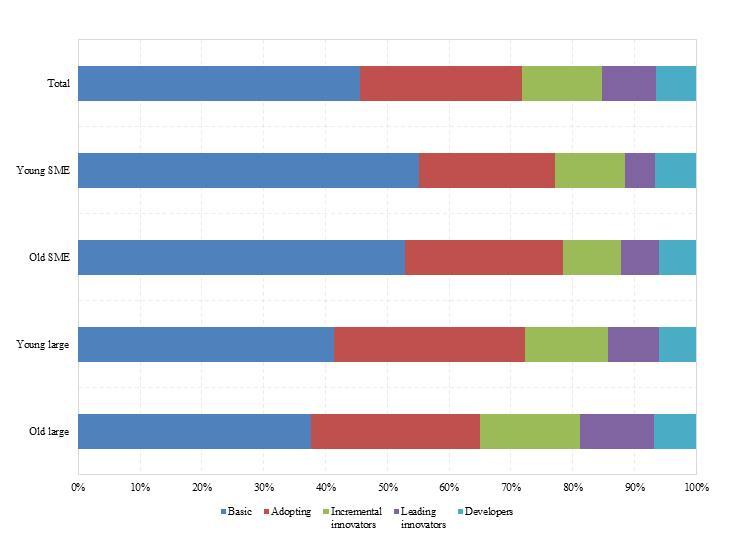

The graphs below show that large, old firms tend to be more innovative than young (less than 10 years old) small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs).

Figure 1: Innovation profiles and firm size (weighted percentages)

Figure 2: Innovation profiles and firm age (weighted percentages)

Figure 3: Innovation profiles grouped by age and size (weighted percentages)

To better grasp what these results mean, we’ll try to link them to the models developed by a leading economist, Joseph Schumpeter, who laid out the basic principles of the economics of innovation at the end of the 1930s. Schumpeter emphasised the role of new entrepreneurs entering niche markets, based on the assumption that small new companies bring to market new and better processes or products, displacing firms with older or less efficient products. By introducing new technologies and by innovating, these entrepreneurs challenged existing firms through a process of “creative destruction,” which Schumpeter regarded as the engine of economic progress.

For this process to work, successful market entrants need to eventually grow big enough to become large incumbents, and the failing firms, in turn, need to restructure or exit the market. There are concerns that this churn may be hampered in the EU. For example, recent research has shown that, compared to the US, Europe has a larger share of static companies – firms that do not grow or shrink – and that this stagnation correlates with lower productivity growth.

Schumpeter also saw a second mechanism for growth: large incumbent firms thriving on their accumulated, non-transferable knowledge in specific technological areas and markets. Our analysis clearly shows that this mechanism (called the Schumpeter’s Mark II Model) is at work in Europe.

If young, innovative firms are missing in Europe, what’s holding them back?

Our investment survey is based on data collected from individual firms. You can’t really ask a firm why it isn’t innovative enough. Instead, we have to look at the differences in the answers of innovative and less innovative firms to some specific questions. A key question we asked was what obstacles were preventing firms from investing (more).

Interestingly enough, the firms with R&D investments were more likely to see a lot of obstacles - presumably because they had actual experience with risky investments. The firms we queried cited many problems, such as difficulty building demand for a new product or service, the availability of financing, uncertainty about the future, and the lack of workers with the necessary skills.

Unfortunately, none of this explains why basic firms remain basic – many of them probably have no need and no motivation to invest in innovation. We should instead pay attention to firms that are innovating despite the obstacles. It is clear these firms see value in innovation. They have innovative ideas, and policymakers in Europe would do well to ask ourselves how we can help these firms innovate more, and with greater impact.

Young innovative SMEs are the most likely to be credit constrained. But we actually get the most insight when we look at old firms. Remember that for the Schumpeterian model of creative destruction to work, small, innovative businesses need to become large incumbents. So if we have talented SMEs committed to innovation, why are some of them still small or medium-sized after 10 years? When we compare them against old large firms, major differences jump out. Almost every other innovative, established SME cites the availability of workers with the right skills and general uncertainty about the future as obstacles to investment. Around one-third of these old, innovative SMEs cite availability of finance, taxation, and business and labour market regulations as hindrances. Old, large firms interviewed cite these concerns less, particularly when it comes to the availability of finance. Altogether, 58% of old, innovative SMEs cite availability of finance as an obstacle to investment, whereas the figure is 40% for old large firms.

Our paper suggests that one way to remedy the situation is to better manage public sector grants. Controlling for country and sector-specific effects, leading innovators are more likely to receive more grants, which confirms the importance of this instrument for EU innovation policy. Small businesses are not more likely to receive grants – if they were, this would perhaps allow innovative SMEs to take off. Innovation policies that aim to increase access to finance need to target young, innovative small businesses.

The problem with the romantic ideal of innovating in your garage is that, at some point, significant innovation costs money – salaries of new employees, equipment and a financial cushion to fall back on when ideas fail. Unless you’ve got bundles of cash stashed away in your garage, your young company may never be able to grow out of it.