The Mohammadi brothers lost a loved one to heart disease, and made finding a solution for predicting heart attacks their life’s mission

By Chris Welsch

The story of Heartstrings begins with an unbearable shock.

Seven years ago, Allen and Max Mohammadi, brothers and engineers in Stockholm, were at a family celebration — the birthday of a cousin. In the middle of the party, their grandmother had a sudden fatal heart attack and died.

“Can you imagine? It went from being a celebration to a funeral,” said Max. “She was 63. She was not overweight. She had never smoked in her life. There was no outward sign of a problem.”

For Allen and Max, their profound grief became a starting point. They wanted to know if there was a way to find out if the same thing might happen to their parents. So they began researching how doctors assess heart health. They were surprised at what they found.

“Heart disease is the number one cause of death all over the world killing one person every two seconds,” Allen said. “According to the World Health Organization, each year more than 17 million people die because of cardiovascular diseases, but in many cases, it’s not the disease that causes the death, it’s the late detection.”

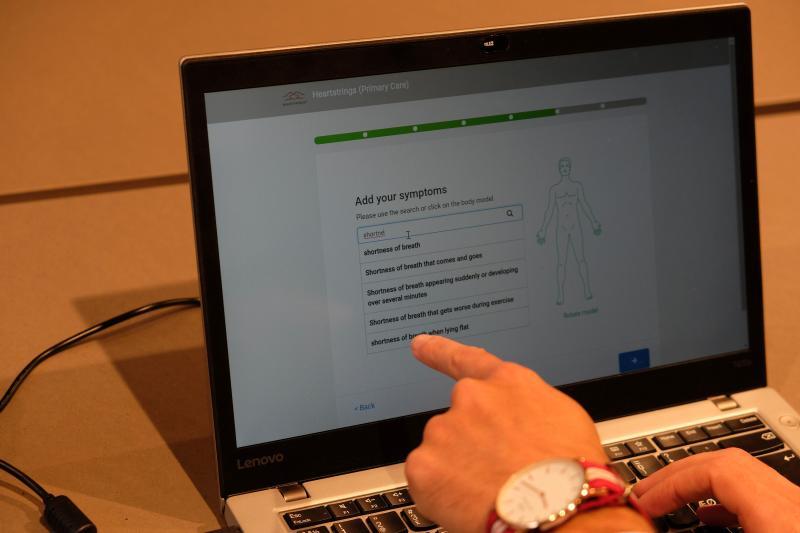

From that personal tragedy was born a burgeoning healthcare business, centred on the screening and early detection of heart disease using a sophisticated software program created by the brothers, called Heartstrings, driven by a proprietary artificial intelligence technique.

Heartstrings is centred on the screening and early detection of heart disease using a sophisticated software program.

Winning the hearts of investors

Heartstrings has captured the imagination of investors and the hopes of many in the healthcare industry.

In 2017, the brothers were winners of the European Investment Bank Institute’s Social Innovation Tournament contest. They were also selected by Forbes magazine as one of the top 30 most influential social entrepreneurs and featured on the prestigious “Forbes 30 under 30 list.” They also won a contest for startups sponsored by the Swedish communications firm Tele2. In tough competition with 4,300 other startups, they won SEK 1 million (or about EUR 100,000) in prize money and the keys to a state-of-the-art office in Södermalm, a trendy Stockholm neighbourhood, complete with full-spectrum lighting, workout equipment and deliberately uncomfortable chairs designed to make it hard to sit still for more than 15 minutes (to encourage standing and moving around).

Before the awards and recognition, Allen and Max faced a long uphill battle to get anyone else to believe in their idea.

Max said that most people find out they have a heart problem only when they go to see the doctor after having symptoms such as chest pain or shortness of breath. But these symptoms may also be related to many other diseases; so thousands of clinical hours are wasted evaluating people who may not even have a heart problem, while as many as one billion people are developing the disease but don’t even realise it.

An engineering approach

“At first and for some time we didn’t have the idea to turn this into a business, we just wanted to find a solution,” Max said.

They approached the issue not like doctors, but as engineers.

“The foundation of our company is built on an engineering mindset,” Max said. Allen continued: “Engineers look at systems and their components. If one component doesn’t work properly, the whole system’s performance will be affected. The human body is also a system and each organ is a component. So we thought by looking at related parameters, we could see if heart disease could be detected at an earlier phase.”

Using a set of different data points— from personal and demographic details to geography and the patient’s medical data collected by nurses and doctors — the brothers created an algorithm using artificial intelligence that could reasonably indicate whether that all-important component (the heart) in the system (the body) was at risk.

At this point, they realised they had an idea that could have a huge social impact — saving lives, saving doctors’ valuable time, saving money as well as making more free beds available, reducing costs for payers (patients, insurance companies, local governments) — while being a sustainable business.

Persistence pays

As they encountered barriers, they found a way over or around.

Having refined their approach, they needed a clinical trial in order to prove their technology, fine-tune their program and address any flaws. But they didn’t have the money to conduct one themselves.

“We spent six months being told no by hospital managers who were saying a clinical trial was too expensive,” Allen said. “But after six months, we met a cardiologist who had a similar problem with her father and she believed in us and our vision.”

She agreed to join the Heartstrings team and carry out the trial with her patients. This was the breakthrough the Mohammadi brothers had been waiting for. With a pool of several hundred patients, the study showed that the Heartstrings technology was better at predicting coronary heart disease than existing tools, and without the need to perform a highly invasive angiography operation.

The system was further refined and is now in use in several hospitals and clinics in Europe and Asia; the brothers are being careful about “scaling up” too quickly, they said. Meanwhile, the program itself becomes more effective the more it is used, thanks to the “machine learning” approach. Because each time a new patient’s data is added to the “brain” of Heartstrings, it learns — rendering it more capable of making the correlations that rule out, or identify, a problem with a patient’s heart.

A broad impact

The brothers started with a goal: to save 1 million lives each year. And by their count, the program has already benefited at least that many people (counting both direct and indirect beneficiaries including patients, their families and healthcare professionals). Now they’ve added another goal — to make Heartstrings available throughout the world, democratising access to what they hope will become a standard procedure in any general physical examination and yearly check-up. They want to make the technology as affordable as possible so that it can be widely used.

“A country like Nigeria has a population of about 190 million people, but fewer than 200 cardiologists. This means Nigeria has one cardiologist per one million people!” Allen said. “But with Heartstrings, even a specialised nurse can collect the data.”

“According to the research, around half of the world’s population older than 40 are developing heart disease right now. So there is a huge demand for affordable and digital technologies to help them,” Max said.

To him and his brother, each of those people have a story like their grandmother’s, and success would be making sure those stories do not have a tragic ending.