By Greg Clark Tim Moonen and Jake Nunley.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Investment Bank.

>> Download the entire essay as eBook or PDF

Europe’s largest metropolitan area has undergone profound changes over the past fifty years, effectively evolving from an under-governed and depopulating national capital to a diverse global centre that benefits from high-quality integrated systems management.

In the 1970s, London felt the effects of deindustrialisation first-hand, as its principal ports moved downstream. As the city’s manufacturing base declined, thousands lost their jobs, setting in train a process of mass emigration. By 1981, over 2 million people had left the capital, and the containment of growth by London’s Green Belt encouraged "leap frog" development into towns far beyond the city limits. The 1970s also saw a cycle of rapid social housing construction, which later became inextricably linked with disaffection, poverty and crime and resulted in outbreaks of violence and rioting into the 1980s.

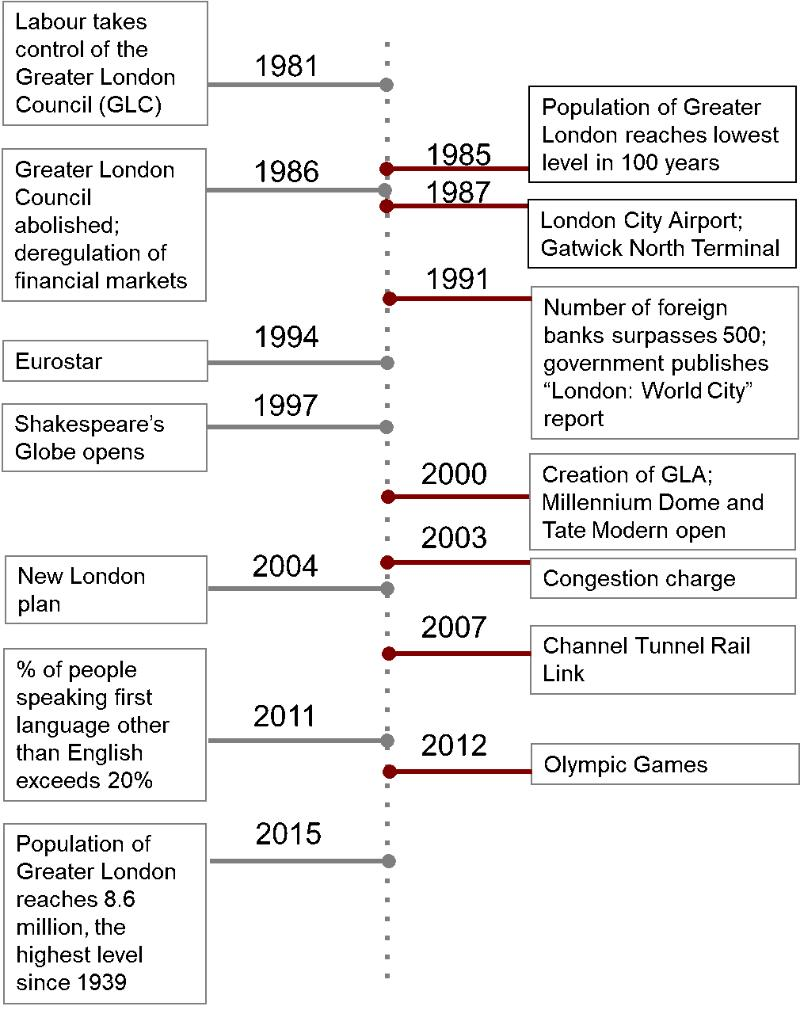

By 1985, London’s population had reached the lowest level seen in 100 years, and in 1986, city-wide government was abolished, leaving the city without a central administration. Recognising the urgent need for action, central government established a new urban development corporation to activate growth in derelict brownfield areas. It was in this context that London became the poster-child of post-industrial development.

This coincided with the "big bang" deregulation of financial markets, which enabled London to leverage its strategic location in the European and African time zone and its proximity to European markets. London quickly established itself as one of the world’s three leading financial centres. By the latter part of the 1980s, population decline had stabilised, and the economy had begun to grow again, as gradual improvements in schools, safety and public spaces began to attract talent back to the urban core. But governance was still a pressing issue, and it was increasingly apparent that the city’s infrastructure was not of a scale or quality that could match its emerging status as a global financial hub.