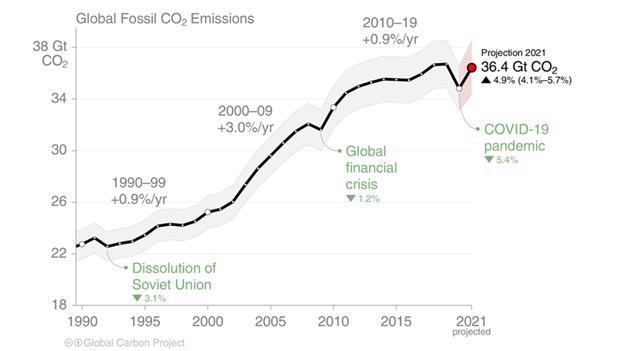

The critical decade requires global economic growth to be fully decoupled from emissions. This has not happened yet – and may still take several years. In this sense, Greta Thunberg has a point. Not all hope is lost, however. Several trends that emerged in 2021 are grounds for cautious optimism about structural change.

2. Reasons for cautious optimism

Three elements stand out from the last year. Firstly, the sheer scope of net-zero pledges across the world. Secondly, the move of sustainable finance into the very centre stage of capital markets. And, finally, the growing appreciation of adaptation at the heart of the international climate finance discussion. These elements will dominate climate finance and policy over the coming years.

Theme 1: Net zero pledges cover (most of) the globe – EU shows the way to be credible

Many countries adopted net-zero pledges in the course of 2021. To be precise, 140 countries have now announced or are considering net zero targets, covering 90% of global emissions5. To those of us who remember the failure of international negotiations at COP21 in 2015, this is truly extraordinary. At that time, most projections were for warming at around 3.7˚C by 2100. With the 2030 NDCs in place, we are now on course for 2.4˚C, and with a shot at 1.8˚C under an optimistic scenario (see Glasgow’s 2030 credibility gap). This is not enough, but COP26 should be seen as a successful round in this larger process, ratcheting up pressure by a notch on global leaders.

Of course, questions can be asked about the credibility of such targets. The European Union has shown the way in this regard. On 29 July 2021, the European Climate Law came into force. It sets a legally binding target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. It sets out the necessary steps to deliver the target, notably with a new target for 2030 to reduce emissions by at least 55% compared to 1990 levels and a series of proposals to revise all relevant policy instruments to deliver this target. It also lays out a process for setting a 2040 target.

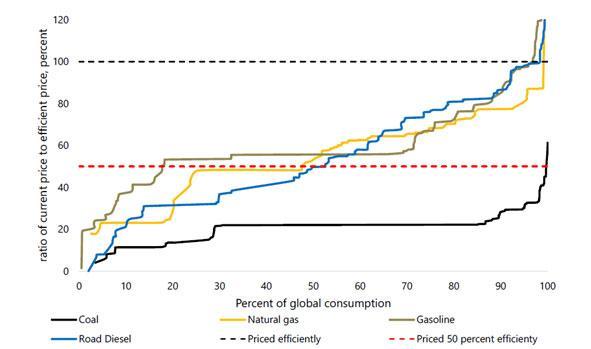

The law provides a general framework. Much EU political capital will be spent in the coming years to agree the detail. This is not surprising given what is at stake, and the potentially important impacts on different parts of society. But the destination is clear. This sends a strong message to markets, as demonstrated vividly in 2021 through the sharp rise in the price6 of emitting a tonne of carbon dioxide within the EU Emissions Trading Scheme to over €80 per tonne. Prices will inevitably fluctuate in the short term, but the expectation of high and rising carbon prices (compared to pre-2020 levels) is now firmly embedded in market expectations.

This price expectation begins to change the economics7 of several technologies likely required to meet net-zero targets, such as carbon capture, utilisation and storage8, or the production of hydrogen9 through electrolysis. Conversely, all companies currently emitting significant quantities of greenhouse gases within the Emissions Trading Scheme bubble need to articulate a growth strategy to investors in a world with a sustained, high carbon price. Leading European companies are doing precisely this – with detailed and credible decarbonisation plans. As many chief financial officers now readily admit, disclosure around corporate sustainability is increasingly central to minimizing the corporate cost of capital.

This is now also the case in terms of accessing European Investment Bank funding. In 2021, the EU bank put forward a comprehensive counterparty framework, notably for corporates engaged in high-emitting activities, or at significant risk from current or future climate change. The framework sets out the minimum requirements the Group expects from corporate alignment plans, including activities that are difficult to reconcile with the goals of the Paris agreement.

In short, for governments that are serious about building credibility, the EU climate law provides a template. The UK and Japan have taken a similar approach. Some may take a different approach – but the very act of having committed to a target will invariably be used to hold future leaders to account by citizens, consumers and voters alike. If there is one country that could do more – simply by virtue of its historic responsibility for emissions – it is the US. It continues to send a mixture of messages. If you are in doubt, watch the sobering testimony given by Carl Sagan to the US Congress in 1985. Then fast forward 36 years to COP26 to see the US unable to join with 23 other countries to commit to phase out coal power.

Theme 2: sustainable finance finally moves to centre stage

In 2021, the EU adopted the EU Taxonomy. The idea is simple and powerful. Deepen the internal EU capital market with clear criteria to label activities as sustainable. In doing so, root out greenwashing. This is achieved through a conceptually simple framework: develop technical criteria to establish that an activity makes a substantial contribution to one environmental objective (e.g. climate mitigation), whilst doing no significant harm to any other environmental objective (climate change adaptation, protection of water resources, circular economy, pollution prevention, protection of biodiversity).

Agreeing on the concept is one thing. Agreeing on actual criteria is, of course, something else. The EU successfully achieved this in late 2021 through the adoption of the first Climate Delegated Act. In doing so, it has certainty caught the attention of the market – as witnessed through the 46,589 responses to the Commission’s consultation exercise. It is also likely to have a direct impact upon project development. In a world with tight financing margins, and against the backdrop of inflationary pressure, developers will explore all channels to reduce their cost of capital. Having a project displaying the EU Taxonomy badge will undoubtedly help. Details will matter, so property developers may well start to pay more attention to performing air tightness tests; or windfarm developers will look more closely at the recycling of key components or resilience to future climate change. Banks and financial advisors are already asking questions. Auditors and the consultancy industry are warming up. This particular train most definitely left the station in 2021.

Having robust definitions for green finance is one thing. But it doesn’t help very much if financiers continue to support other types of investment that is difficult to reconcile with the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement. This concept of alignment is increasingly being put into practice, perhaps best demonstrated at COP26 by the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, an initiative from signatories overseeing $130 trillion to set clear targets and timelines for green investments. This includes 98 banks across 40 countries with 43% of global banking assets, or $66 trillion. This scale matters10: The International Energy Agency estimates global annual investment to meet net zero at around $5 trillion.

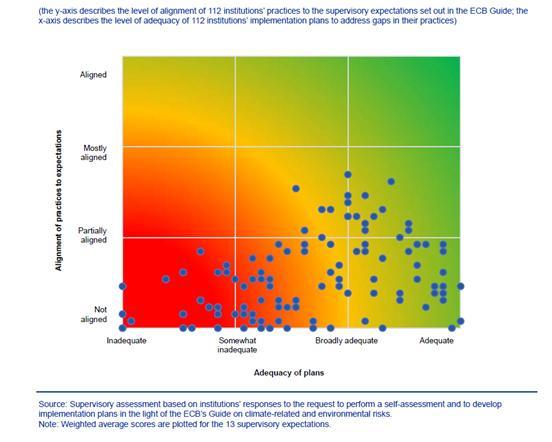

The rise of sustainable finance is to be welcomed. But we should not get too carried away yet – much work remains. In November, the European Central Bank published a supervisory review of banks’ approaches to managing climate and environmental risks. The result? Based on a self-assessment conducted by 112 significant institutions, not one is close to aligning fully their practices with the supervisory expectations.