Our Economics department keeps track of all the important developments in the financial markets in both advanced economies and emerging markets. We are publishing periodic briefings with analytical assessments of the current macroeconomic and financial market situation. Find out more about the EIB Group's response to the crisis

Overview

EU economy - GDP decreased by 3.5% in the European Union (3.8% in the euro area) in the first quarter of 2020 compared to the previous quarter (q-o-q). At the country level, France's GDP dropped by 5.8% q-o-q, Spain's GDP by 5.2% and Italy's by 4.7%, These are the most significant quarterly falls since the GDP series collection began. Expectations for the second quarter remain gloomy. This is confirmed by the EIB economic department's coincident indicators, the flash purchasing managers' index (PMI) indicators and the European Commission's Business and Consumer sentiment indicators in Europe: these indicators all deteriorated in April, with a significant worsening of the expectation component for the next three months. More than 20 million European workers from Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom, about a fifth of all workers, are currently on temporary work schemes. All in all, a U-shape recovery seems a likely outcome.

Although rating activity was somewhat lower lately, Fitch downgraded Italy to BBB- on 28 April on account of the severe economic impact of COVID-19 on the economy and the associated worsening of the debt sustainability outlook. The market reaction was muted. S&P confirmed Italy's BBB rating on 24 April.As the crisis persists and the impact on public finances and economic performance continues to worsen, more downgrades, including for the European Union, can be expected during the coming weeks.

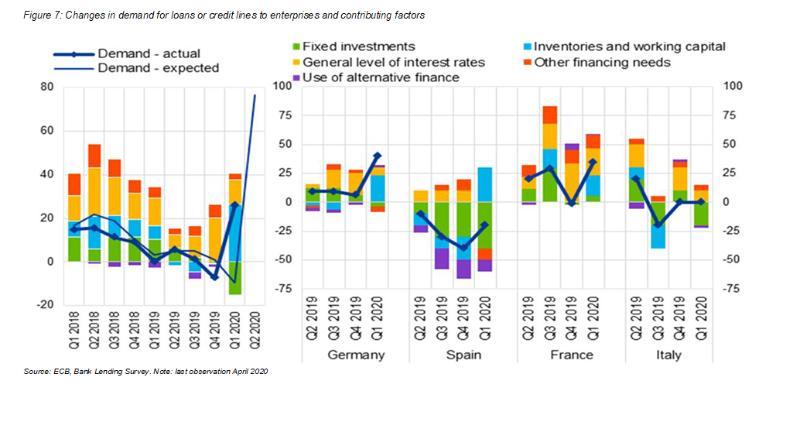

Euro area banks report higher demand for credit from enterprises and future easing of credit standards. This reflects higher liquidity appetite by corporates and the numerous policy measures introduced by governments and regulators to help alleviate credit standards. This situation is likely to persist in the second quarter, according to the April Bank Lending Surveyby the European Central Bank (ECB). That said, country heterogeneity is quite evident. We observe a dichotomy in funding conditions for corporates. While there are some early signs of gradual improvement of funding conditions for larger corporates, which can also benefit from the ECB's bond purchase program, smaller enterprises with no access to market finance still encounter major difficulties, in particular in certain sectors.

Emerging Markets - Turning to emerging markets, market sentiment remains weak, albeit with slight improvements compared to the past couple of weeks. Some early signs of stabilisation were mainly driven by the generally positive news about the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic in major advanced economies, along with announcements of a gradual unwinding of containment measures and additional policy interventions. That said, emerging markets' vulnerability to the economic fallout of the pandemic and their capacity to respond remain a cause for concern, in particular with regard to debt sustainability.

Policy responses, focus on the European Union - Policymakers across the European Union have taken swift action to mitigate the impact of the pandemic. The focus has been on the short term, including measures to contain the spread of the virus, support medical care and maintain economic structures. On top of national measures, EU leaders agreed on a common response package amounting to a total of EUR 540 bn to fight the consequences of the pandemic, including a) a pandemic crisis support instrument managed by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), b) support via the European instrument for temporary support to mitigate unemployment risks in an emergency (SURE), helping to boost member states' efforts to protect employment and c) a EUR25 bn guarantee fund at the EIB to support European companies, particularly SMEs, with up to EUR 200 bn. Moreover, the Commission was tasked to prepare plans for a recovery fund in the context of a revision of the multiannual financial framework. The discussion is still very open in terms of recovery strategies and policy priorities looking ahead.

The authors of this note are: Simon Savsek, Joana Conde, Andrea Brasili, Matteo Ferrazzi, Aron Gereben, Laurent Maurin, Ricardo Santos and Patricia Wruuck. Reviewed by Barbara Marchitto and Pedro de Lima. Responsible Director: Debora Revoltella.

1. Latest economic developments

The European economy is on its way toward a deep recession. GDP decreased by 3.5% in the European Union (3.8% in the euro area) in the first quarter of 2020 compared to the previous quarter (Figure 1). In annualised growth terms, the fall is -14.4%, three times as large as in the United States (-4.8%) reported on 30 April. At the country level, France's GDP dropped by 5.8% q-o-q, Spain’s GDP by 5.2% and Italy’s by -4.7%, all largest falls since the GDP series collection began. Our coincident indicators1 (intended to summarise short-term dynamics) for April also shows a definite worsening at the beginning of the second quarter for all the four countries (Figure 3). The decline is particularly steep for Italy, where the index in April is well below the (relative) minimum reached during the 2012 recession. Moreover, the two-month cumulative drop between February and April is as big as the drop between June and December 2008, the seven months that marked the beginning of the global financial crisis in the second half of 2008. For Germany, the monthly decline in April is second only to the ones recorded in November and December 2008. The dataset is still mainly populated by survey results (PMIs and European Commission surveys) even though some hard data has been included: car registration, retail sales and exports. Turning to the European Commission surveys, the Economic Sentiment Index (ESI) plunged in the Netherlands (−32.6), Spain (−26.0), Germany (−19.9), and France (−16.3), while no data was collected in Italy due to difficulties linked with the confinement measures. Industrial confidence fell dramatically (−19.2), but remained above the record low of March 2009, while for services the indicator dropped (-32.7) to its lowest level on record driven by record-breaking deteriorations in expected demand.

Zooming in on sectors, the Flash Purchasing Manager's Indexes (PMIs) for April confirmed not only the freefall started in March, but also that services are taking the heaviest blow. The PMI dropped to 13.5 from 29.7 in March in the euro area, the largest monthly decline on record (Figure 2). Manufacturing also showed the impact of supply chains disruptions and shortages of inputs. In Germany, the ifo business climate survey is pointing further down and moved to 74.3 in April from 85.9 in March and 96.0 in February, alongside deteriorating expectations. In France, economic activity is currently about 35% below normal conditions, according to a report by INSEE, the French statistical agency. In particular, activity in the business sector and consumer spending are 41% and 33% below normal conditions, respectively.

Expectations over the next three months - across all subcomponents of the Economic Sentiment Indicator - deteriorated drastically, signalling that a very severe downturn in the second quarter of 2020 is to be expected. It should be noted that, compared to previous months, the response rate was lower, thereby limiting the comparability of the index and possibly signalling even sharper actual declines. Focusing on the more forward-looking components of the report, the graph below shows the worsening of expectations in terms of production for manufacturing (Figure 4) and demand for services in the European Union (Figure 5), disaggregated by sector. The ranking is relatively unchanged from the previous month, with the sectors directly affected by the lockdowns (hotels, restaurants, travels and leisure) suffering the most; but worsening expectations are mounting in other sectors as well, showing that a sgeneralised recession is ongoing.

Despite government support, employment prospects are grim amid sharp contraction of economic activity. More than 30 million workers from the five largest economies applied to have their wages paid or subsidised by the state: about 10 million in France, more than 7 million in Italy, about 5 million in Germany and 4 million in Spain and UK. This represents about 20% of the total employment combined in these countries. Measures to prevent job shedding are among the most expensive introduced by European governments, as they are expected to cost more than EUR 100 billion in total in these five countries as reported by the Financial Times on 28 April. In Japan, the unemployment rate increased to 2.5% in March, while the ratio of open jobs to applicant fell sharply to 1.39, the lowest since mid-2016.

1. See Weekly of April 8 for methodological descriptions of the indicator.

2. Financial Markets

Sovereigns

The COVID-19 crisis is hitting sovereign creditworthiness across the world. As a result, the three main credit rating agencies downgraded numerous countries, and their activity is well above the 2019 average (Figure 6). On on 29 April, Fitch downgraded Italy to BBB- from BBB on account of the severe economic impact of COVID-19 on the economy and associated worsening of the debt sustainability outlook (the market reaction was, however, muted). On 24 April, S&P confirmed Italy's sovereign rating at BBB, arguing that although public debt is set to reach 153% of GDP by end-2020, the ECB provides an efficient backstop for the required additional borrowing. Although no other EU country was downgraded (the UK was downgraded to AA- with negative outlook by Fitch in March), nine had their outlook lowered in March and April by at least one of the agencies (Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Latvia, Malta, Portugal and Romania). It is worth recalling that the ECB introduced measures to mitigate the effect of rating downgrades on collateral availability and eligibility for the asset purchase programmes, and thus ECB monetary policy transmission, to prevent potential pro-cyclical dynamics. More specifically, the ECB announced on 18 March that Greek government bonds would be included in the new public sector asset purchase program (PEPP), despite their lower rating. More recently, on 22 April, the ECB announced that it would ease the minimum rating requirements for collateral from BBB- to BB at least until September 20212.

Banking sector

Euro area banks report higher demand for credit from enterprises and lower demand for housing loans, according to the latest ECB euro area bank lending survey (BLS). The results show an increase of loan demand by enterprises in the first quarter of 2020 and an expected increase in the second quarter, largely driven by emergency liquidity needs (Figure 7). Demand for housing loans shows the opposite trend, with a deceleration in the first quarter and a sharp fall expected in the second quarter of 2020 (a net percentage of 6.7% of banks expect a decline, similar to what was registered in the second half of 2008). This aggregate picture masks significant differences across countries. While net demand for loans to enterprises increased considerably in Germany and France in the first quarter of 2020, it declined in Spain and remained unchanged in Italy (Figure 8). Demand for housing loans also showed some divergence, increasing in Germany and France and decreasing in Spain and Italy.

Banks report tighter credit standards on loans to enterprises in the first quarter but expect a substantial easing in the second quarter of 2020 (Figure 8). Still, the tighter credit conditions reported by euro area banks are relatively contained when compared to the tightening of bank credit standards during the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis. According to the ECB, this more muted reaction is related to the size and timeliness of policy measures and the greater resilience of euro area banks. In the second quarter, banks expect credit standards to ease considerably for firms due to the support measures introduced by governments (guarantee schemes) and the ECB. Credit standards on loans to enterprises tightened in the first quarter of 2020, especially in Germany, followed by Italy and Spain, while they remained unchanged in France. For housing loans, credit standards tightened in Germany and particularly in France (partly due to macroprudential recommendations), but remained unchanged in Spain and Italy.

Corporate sector

In Europe, after extreme rapid gains during the first half of March, non-financial corporate bond yields have since been on a declining trend, from around 160 bps to 130 bps for BBB-rated corporates and from about 120 bps to 80 bps for A-rated corporates (Figure 9). Overall, one-quarter of the rise recorded since the onset of the crisis has been reversed. As for the rise, the decline in corporate bond yields has been relatively similar across the rating spectrum. However, many corporates have faced downgrades and therefore issue at yields associated with higher risks. Overall, it is difficult to assess the evolution of the cost of debt finance: it is reduced by the lower price of risk but increased by the higher risk. In late April, 70% of the outstanding amount of debt issued by non-financial corporates is rated below investment grade (Figure 10).

Stock prices of non-financial corporates have also continued their rally from their low of late March. Since then, one-third of the losses has been recovered, from a low of -30% compared to December 2019, to -20% in the last week of April. Conversely, since late March, bank stock prices have continued to decline and currently stand between 40% to 45% below their levels of December 2019.

Economic sectors have been affected unevenly by the crisis. Stock markets have priced in – since the beginning of 2020 – a steeper decline for industrial goods and automobiles than for any other sectors. On the opposite end of the spectrum are pharmaceutical and health care services, which have not only rebounded from the overall late March low but are currently above December 2019 levels (Figure 11).

Similarly, small corporates without access to market finance have also been affected differently across sectors. As shown in Figure 12, the median cash to sale ratio of corporates varies substantially from a low of 25% in pharmaceuticals to a high of 85% in real estate. For a given cost structure, firms with higher cash buffers can withstand a longer period of sales freeze. In contrast, firms with weaker cash positions may have to tap overdrafts, an extremely expensive funding source, sooner. However, cash positions also reflect features of the business model specific to each firm and sector. Therefore, without considering characteristics of the cost structure, it is difficult to gauge the impact of the differences in cash position on liquidity risk. To reduce the likelihood that European corporates fall into bankruptcy owing to liquidity shortfall, policymakers in the European Union have designed various programmes to alleviate cash outflows and maintain the flow of short-term credits.

Emerging markets

Market sentiment towards emerging markets remains weak, albeit with slight improvements compared to the past couple of weeks. Some early signs of stabilisation were mainly driven by the generally positive news about the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic in major advanced economies along with announcements of gradual unwinding of containment measures and additional policy interventions. This is also reflected in an improvement in market volatility - VIX (Figure 13) – and the stabilisation of capital outflows from the emerging economies, which plateaued at around USD 90 bn (cumulative since end-2019) in the second half of the month. That said, divergences among emerging markets are growing larger, with Latin America, sovereign spreads, currencies and stock market falling behind emerging market average, driven by Mexico and Brazil (Figure 14).

Notwithstanding the recent, relatively more benign mood in the financial markets, economic costs for emerging market economies appear to be on the rise, reflecting the implementation of more stringent measures to halt the spread of the disease. To support economic activity, emerging market governments undertook a range of monetary and fiscal policy actions in the last two weeks. On the monetary side, Turkey cut borrowing costs by twice as much as predicted by investors; Mexico slashed its key rate in an emergency meeting; the Ukrainian central bank lowered rates below 10% and the Russian central bank cut its benchmark lending rate by 50 basis points to 5.5%, their respective lowest levels in six years. As for fiscal measures, the most striking example comes from South Africa, which announced an additional package of USD26bn (10% of GDP). However, markets reacted negatively to the majority of these announcements, a potent reminder that economic authorities in emerging economies are relatively more constrained in sutilising economy policy tools to mitigate the effects of the crisis.

Emerging and frontier market sovereigns and banking systems continued to suffer from rating downgrades or outlook changes. In the last two weeks, Moody's changed the banking system outlooks of South Africa, Nigeria, Morocco, Brazil, Colombia, Paraguay, Panama and Uruguay from stable to negative, quoting an expected rise in non-performing loans and a protracted decline in banks' profitability. On a positive note, Moody's assessed the liquidity positions of those banking systems (in both domestic and foreign currency) as resilient, given the support provided by the respective Central Banks. Nigeria is the only noted exception.

2. For more details and exact wording see https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2020/html/ecb.pr200422_1~95e0f62a2b.en.html

3. Policy measures – where do we stand?

Policymakers across the European Union have taken swift action to mitigate the impact of the pandemic. The focus has been on the short-term, including measures to contain the spread of the pandemic, support medical care and maintain economic structures. The discussion is still open in terms of recovery strategies and policy priorities looking ahead.

EU leaders agreed on a common response package amounting to a total of EUR 540 bn to fight the consequences of the pandemic. On 23 April the European Council endorsed a set of instruments to mitigate the pandemic shock. Three safety nets for sovereigns, workers and firms will be put in place. These operate through i) a pandemic crisis support instrument managed by the ESM, ii) support via SURE, helping to boost member states' efforts to protect employment and iii.) a EUR25 bn guarantee fund managed by EIB to support European companies, particularly SMEs, with up to EUR 200 bn. In the concluding statement by the President, Members of the European Council have called for the package to be operational by 1 June 2020. Additionally, the Commission is reportedly working on a recovery fund of sufficient magnitude to provide targeted sectoral and geographic support to the parts of Europe particularly affected. In the following section we take stock of the size and the areas of policy measures that EU countries have put forward, both at national and EU level. First, we discuss policies that addressed the acute – health and economic – emergencies; then we focus on what remains to be done to support the post-crisis recovery.

At the Governing Council meeting held on 30 April, the ECB announced new measures, re-calibrated some of the previous measures and re-iterated the commitment to increase the size of the PEPP and adjust its composition by as much as necessary and for as long as needed3. More specifically: (i) the conditions on the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) have been further eased, (ii) a new series of non-targeted pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing operations (PELTROs) will be conducted to support liquidity conditions in the euro area financial system and contribute to preserving the smooth functioning of money markets by providing an effective liquidity backstop, (iii) operations under the new pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), which has an overall envelope of EUR 750 billion, will continue to be conducted in a flexible manner over time, across asset classes and among jurisdictions at least by the end year, (iv) net purchases under the asset purchase programme (APP) will continue at a monthly pace of EUR 20 billion, together with the purchases under the additional EUR 120 billion temporary envelope until the end of the year, (iv) reinvestments of the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP will continue in full according to the specified conditions, (v) the interest rate on the main refinancing operations and the interest rates on the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility will remain unchanged at 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.50% respectively.

Short-term priority: emergency response

With COVID-19 as a symmetric shock, member states – supported by EU-level instruments - have deployed rather similar policy mixes (but different sizes of intervention) to mitigate the short-term social and economic consequences of the pandemic. Member States have rapidly deployed targeted fiscal measures and liquidity schemes over the last weeks. Policy responses focus on common themes such as boosting capacities in the health sector, supporting companies through loans and guarantee programs and tax measures, maintaining employment and mitigating social hardship for citizens, as well as measures supporting the financial system. In the European Union, support packages vary in size and design but also in the current status of implementation4. European responses tend to rely more heavily on guarantee instruments than other major economies such as Japan or the United States.

Health and containment measures. Health measures to contain the spread of the virus, improve monitoring and support treatment form the first line of defence against the pandemic, and show the potential for complementarities between national and EU actions. Most member states diverted additional spending to healthcare over the last weeks to shore up resources, regardless of their respective healthcare system capacities and fiscal space. This includes increased spending on immediate measures to fight the pandemic, ramping up health supplies and purchasing equipment such as testing kits or ventilators, additional compensation for health workers, financial support for hospitals and funds to develop medicines and vaccines.

At the EU level, health measures are supported through the Coronavirus Response Investment Initiative, which allows rechanneling unused resources from the structural and cohesion funds to first-line defence, among other objectives. The EU Solidarity for Health Initiative was launched to support member states' healthcare systems with approximately EUR 6bn. Furthermore, the European Union supports member states' health and containment efforts through administrative measures and coordination. These include joint public procurement mechanisms for medical equipment, setting up coronavirus testing guidelines, establishing an EU "clearinghouse" for medical equipment, restrictions on exporting medical supplies outside the European Union, lifting customs duties on imports of crucial supplies, and coordination of cross-border healthcare cooperation, including the facilitation of the transfer of patients from one member state to another.

Measures targeting firms. All countries have put in place financial support to firms affected by the demand shock and measures to help preserve employment and incomes. Support to firms comprises both loan and guarantee schemes to address liquidity needs and tax measures, including tax deferrals or reduced tax rates for particularly hard-hit sectors. Almost all member states implemented public loan and guarantee support schemes focusing on working capital and the availability of the support for both SMEs and larger corporates. The vast majority of countries has also put in place support measures for self-employed. Some countries, such as France and Germany, also implemented programmes dedicated to start-ups and innovative companies. This is also one area where EU-level action has been applied to reinforce and broaden national efforts, such as the setting up of a EUR 25bn guarantee proposed by the EIB.

Besides loans and guarantees, a majority of member states also provides support in the form of grants to corporates, often with a focus on smaller firms and the self-employed. In addition, tax measures are used to ease corporates' liquidity and support particularly hard-hit sectors such as tourism, through tax holidays, deferrals or reduced taxation rates. Other support measures include credit moratoria and automatic rollover existing working capital loans.

Support to employment and social policy. A crucial component of the enacted policy responses are measures aimed at supporting employment, notably through the use of short-term work schemes that help firms to adjust working hours while preserving jobs. Public income support permits employers to hold on to staff and restart production quickly once activities can resume. Short-term work (STW) schemes can be an effective way to mitigate the economic and social costs of a major economic crisis, notably if the drop in demand is expected to be temporary. First indications show that while STW schemes are being used extensively, their use has most likely not peaked yet. To that extent, the EU-supported program SURE acts as a second line of defence, helping member states to address the sudden increase in expenditure as a result of STW scheme use.

Maintaining employment can also mitigate the further deepening of inequalities as a result of the pandemic shock. However, it should be noted that while most member states operate STW schemes, institutional differences remain in the way costs are shared between governments, firms and workers and in conditions for participation. When it comes to specific social measures, most member states have taken actions to support vulnerable persons, including income support for quarantined workers who cannot work from home, and help to deal with unforeseen care needs or special income support for sick workers and families. In some member states, credit moratoria or payment deferrals of rent or energy bills are used to support households' liquidity needs. From an EU-wide perspective, there is considerable heterogeneity across the range of implemented social measures, reflecting the diversity of, existing social systems and social policy approaches. Altogether, the aim, choice of key support instruments – loans, guarantees, tax measures and STW – and measures taken, indicate a joint understanding of short-term needs to fight the pandemic, to support corporates and to maintain employment, with EU measures complementing member states' efforts.

Financial system and monetary policy. Financial and monetary measures substantially support the common response within the Eurozone, with policies in non-Eurozone member states broadly aligned. The functioning of the system of financial intermediation is critical during the crisis and for the subsequent recovery. First, the financial sector acts as an intermediary for many of the measures targeting corporates and individuals. Second, a spillover of the crisis into the banking system would amplify its negative impacts. Third, a functioning banking system is necessary to support the post-crisis recovery through financing investment needs.

Ensuring ample liquidity and capital in the banking system has been a priority since the beginning of the crisis. Since the previous crisis originated from the banking sector and policy measures have been taken in response, the EU banking system is now better prepared, both in terms of balance sheet health, and when it comes to safety nets. To ensure adequate liquidity in the banking system, the ECB introduced a range of new measures (see above).

EU central banks outside the Eurozone implemented similar measures (targeted long-term refinancing, bond purchase programmes, easing of collateral regulations). In some countries, such as Poland, Czech Republic, Romania or Sweden, these measures were complemented with interest rate cuts. However, some Central and Eastern European countries have been already facing capital outflows, and their currencies weakened since the beginning of the outbreak5. In such circumstances, central bank liquidity injections and monetary policy easing can amplify the pressure on the exchange rate. Thus, if capital outflows strengthen, it may pose a dilemma for monetary policy in these countries and countries may have to navigate between the conflicting goals of liquidity provision and exchange rate stability.

On the capital side, measures by the Single Supervisory Mechanism and national supervisors have been adopted to preserve the strong capital position of the EU banking system and the flexible use of existing buffers. These include dividend and share buyback freezes, the relaxation of macro-prudential buffers, the flexible use of the various capital buffers. Furthermore, regulators have initiated actions to ensure that measures targeting the corporate sector do not put an unnecessary excess burden on banks.

The ECB has agreed to swap line arrangements with some EU central banks to provide euro liquidity and is assessing further requests for euro-providing swap lines. This is part of a coordinated action of major central banks (i.e. ECB, FED, Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, and the Swiss National Bank) to enhance the provision of US dollar and euro liquidity. On 15 April, the ECB agreed to provide a EUR 2bn currency swap line to the Croatian central bank for additional liquidity, with maximum maturity for each drawdown of three months. A similar agreement was concluded with Bulgaria on 22 April. Earlier in March the ECB reactivated its pre-existing swap line with the Danish central bank, and increased the maximum amount to be borrowed by the Danish central bank from EUR 12 bn to EUR 24 bn. The swap lines will remain in place at least until end-2020 or as long as it is needed.

At this point, the implementation speed of policy responses is crucial. The implementation speed of the emergency measures is critical, not only to support health systems' still under strain, but also to address firms' urgent liquidity needs. While EU countries show similarities in the type of measures, the speed at which the measures have been announced and implemented show significant differences. Although it is difficult to make a complete assessment at this stage, the differences are evident. For instance, Bpifrance reported that by mid-April 150,000 enterprises had received pre-approval for emergency financing, for a total of EUR 22bn, while the Hungarian Development Bank announced the details of its guarantee and loan programmes only during the second half of April.

Long-term agenda: supporting a robust recovery

Looking beyond measures to tackle the acute phase of the crisis, plans for the recovery are yet to be streamlined. The European Council tasked the Commission to establish a recovery fund of a sufficient magnitude, targeting the most affected sectors and geographical parts of Europe.

Policy priorities for a recovery agenda are difficult to pinpoint at this stage, but early preparation is vital. We believe the following elements are essential to support a rapid and robust rebound of the EU economies in the aftermath of the pandemic.

- Combine policy focus with the need for 'smart' and 'green'. Public investment can be a crucial element of a fiscal stimulus package, and one that can be implemented at the EU level. Both public investment and broader economic policy needs to keep the focus on the long-term structural challenges faced by the EU economies, such as sdigitalisation and climate change mitigation. Maintaining momentum for Europe's existing pre-pandemic long-term political and economic priorities will be paramount in the post-COVID-19 recovery. Notwithstanding the current emergency, these areas are the foundations of the long-term competitiveness and growth potential of the EU economies. The EU recovery plan must take that into account, and public spending should foster these objectives beneath general demand support. It is also important to highlight that the COVID-19 crisis further amplifies the social and labour market challenges and transformation needs associated with sdigitalisation and climate change; therefore, active policies mitigating the labour market and social impacts of the digital and climate transition must be reinforced and accelerated. Given its role in supporting innovation and transformation, and because of its substantial long-term benefits, education is also one of the areas with room for further support.

- Fixing the labour market. The shutdown of economic activity and its spillover effects are causing severe disruptions on the labour market. Even with mitigating policies in place, many jobs will be lost, and a disproportional impact of the pandemic shock stands to impact more vulnerable groups in the labour market. It is imperative to implement measures that speed up matching in the labour market in the aftermath of the crisis. Hiring (and training) subsidies for firms may provide a valuable incentive to absorb the unemployed back to the job market. Training programmes and other active labour market policies would help to address mismatches between labour demand and supply.

- Preventing deterioration of balance sheets now and repair them as a matter of priority later on. Most of the policy response now is aiming at injecting liquidity in the system, preventing major deteriorations in credit quality and keeping the credit flows going, by providing state guarantees for companies and banks. But past crises show that a protracted crisis will lead to increased bankruptcies and non-performing loans. Lessons from past crises have shown that the speed of recovery depends heavily on the speed of clearing balance sheets and debt overhangs, both for corporates and banks. Bank supervision and regulation will thus have to encourage the recognition and resolution of non-performing loans through strengthened insolvency frameworks and development of markets for distressed debt.

- Pre-define exit strategies, to take place in due time, to protect the single market. While targeted emergency measures are essential during the crisis phase, their timely and orderly phase-out is equally important. First, the scale-back can free up fiscal space for a broader stimulus. Second, explicit exit strategies can limit the moral hazard associated with some of these measures, such as low-cost blanket guarantees and payment moratoria. Third, measures that allow flexibility in providing state aid may provide incentives for governments to support national companies at the expense of similar firms in other member states, which would bring distortions to the single market.

- Reacting to shifts in preferences. While supporting the recovery, public policy must take into account the impact of the crisis on social preferences. The pandemic and its consequences will leave their mark on habits, social norms, the world of work and production, and more. For instance, telework and videoconferencing are likely to be more widespread than before. Such shifts are difficult to predict, but they need to be accommodated when designing public policy.

Fiscal space will be even more constraining for the recovery phase. While fiscal sustainability issues became naturally less visible under the current circumstances, they will resurface forcibly during the recovery. Substantial differences in fiscal room and deficit accumulation among EU countries will matter when it comes to supporting the post-crisis recovery. Countries with a lower initial debt position will be able to provide ample support to kick-start their economies, while those who entered in the crisis with already high levels of public debt will have minimal options to support aggregate demand, and will be more likely to face a protracted recovery.

This calls for joint EU-level action in the form of a recovery fund. The rationale for joint action goes beyond solidarity. The high level of economic integration in goods and services markets, value chains, capital markets and labour flows all add to EU-wide welfare. Both negative and positive spillovers from individual member states are impacting on the European Union as a whole. Without a common mechanism, the recovery in the Union will take longer and will be uneven. An uneven recovery would contribute to further divergence across member states, weakening the various components of the single market. Also, it could aggravate imbalances in the fiscal-monetary policy mix. An uneven recovery would also slow down the long-term structural transformations (digitalisation, climate change mitigation) that are key to the long-term competitiveness of the EU economy. Furthermore, it would amplify the existing social inequalities. A lengthy and uneven recovery with insufficient EU-level support could erode the social and political support for the European Union impose some additional hardship on the European project.

3. For more details and exact wording see https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2020/html/ecb.mp200430~1eaa128265.en.html

4. For further discussion, see for instance IMF Fiscal Monitor April 2020.

5. Since the beginning of the year, the Hungarian forint depreciated by 7.3%, the Czech koruna by 6.7%and the Polish zloty by 6.4% relative to the euro.

4. Conclusions

New data releases continue to confirm that, in addition to its dramatic human toll, the economic fallout of the COVID-19 crisis is going to be extremely severe, possibly the worst since World War II. Consumer and investor sentiment and expectations seem to suggest that the sharp drop in economic activity is likely to continue in the coming months.

Against this backdrop, the strong policy response designed at the EU level and by EU Members States must be implemented timely and with resolve to make sure that much-needed support is channelled as soon as possible to European households, workers and entrepreneurs hit by the crisis.

Going beyond the emergency, the policy response should be far-sighted and aim not only for more growth after the crisis, but also for better growth, enhancing the EU economic potential, supporting smart and green investments, strengthening our human capital and offering opportunities to innovate.