Iceland uses its volcanos to produce energy and fight climate change

Icelandic author Hallgrimur Helgason writes that “Europe and America are slowly drifting apart. Iceland is the only thing that can possibly keep them together.” In fact, Iceland is literally split in two by tectonic plates, the very product of continental drift. In few places in the world is the physical separation of continents as visible and scenic as in Iceland, where the North American and Eurasian plates move apart by two centimetres each year.

Resourceful Icelanders like engineer Marta Rós Karlsdóttir find in the changing forces of nature the power to run their cold and isolated land.

“We are so lucky here in Iceland,” Marta says. “We have outdoor swimming pools and warm homes all year long, even in freezing weather and snow. We owe it all to the geothermal resources and the special location of our country.”

Innovative Icelanders such as Marta Rós Karlsdóttir make the most of unique natural resources

Fact one: All the energy produced in Iceland comes from renewables

A 34-year-old mother of three, Marta is managing director of natural resources at ON Power, the country’s leading producer and supplier of energy. She proudly explains that today all the energy produced in Iceland comes from renewable resources – mainly geothermal and hydropower.

Much of that energy comes from Hellisheidi. Located right on top of the Hengill volcano in the south of Iceland, Hellisheidi is one of the largest geothermal power plants in the world.

Steam generated by volcanic heat two kilometres beneath the ground welcomes visitors at Hellisheidi, one of the largest geothermal power plants in the world

“Around two kilometres beneath the ground we have a geothermal reservoir coming from the rain slipping through the rock and meeting the hot lava of the volcano,” says Marta. “This creates a mixture of steam and water that we collect through deep wells.”

The Hellisheidi team uses this resource to produce electricity for 75 000 homes and 10 000 businesses in Iceland.

Fact two: Geothermal waste heat is put to good use - hot water and famous lagoons

Besides producing 10% of the electricity in Iceland, the largest geothermal power plant in the country also provides hot water to cover part of the heating demand of the Reykjavik region (and there is a lot of demand in a country where heating is needed even in summer). How? By using the waste heat from electricity production.

“Once we have taken out the steam and hot water to generate power and hot water, we reinject the remaining geothermal water back into the ground, forming a kind of loop of renewable energy. We do this to protect the environment but also to keep our precious resource sustainable,” Marta says.

Many other geothermal plants discharge this water on the surface, often forming large outdoor hot pools. Actually, the water of the world-famous Blue Lagoon is a by-product of a nearby geothermal power plant built in 1976. In the years that followed, people began to bathe in the unique, milky-blue water. Today, the Blue Lagoon is Iceland’s top tourist attraction.

Fact three: Iceland has developed a climate action breakthrough

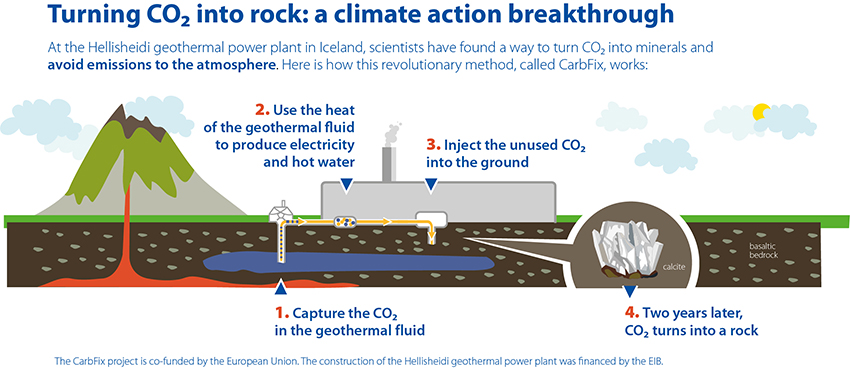

If you have trouble finding the exact location of a geothermal plant, follow your nose. These plants generate up to 95% less CO2 emissions than conventional thermal power plants. Still, they emit steam, some gases with a peculiar smell, and also greenhouse gases. In Hellisheidi, an innovative research project that made headlines around the world aims at developing a safe, simple and cost-effective method to bury CO2 emissions underground. Its name is CarbFix.

“Ours scientists found out that due to the nature of the volcanic rock here, it was possible to get the small amount of CO2 that travels with the geothermal fluid from the ground and reinject it back where it came from. Once underground, the CO2 forms minerals that get fixed to the rock, permanently avoiding the emission to the atmosphere,” says Marta Rós.

And it worked. Only two years after being buried near Hellisheidi, the CO2 had crystalised. “It is a unique process, applicable in many places around the world, especially in the numerous areas with basaltic rocks below the sea. The CarbFix method is one of the tools we can use in the battle against climate change.”

Fact four: Yes, I said three things, but…

Although working with a volcano is not easy, things are more manageable when you have the right financing in place. In the last 20 years, the EU bank has lent a total of EUR 150 million to build and expand Hellisheidi and other geothermal energy facilities in Iceland. “The European Investment Bank has been our biggest lender since 1997,” says Marta.

The construction of Hellisheidi was one of the projects financed through the proceeds of the world’s first green bond issued by the EIB 10 years ago.

The most recent loan, signed in 2016, will help sustain the green energy production levels by allowing the ON Power team to drill additional wells, and connect the facility to new large distribution pipelines. The loan will also cover environmental projects such as the reduction of emissions of geothermal gases to the atmosphere.

“Managing a geothermal resource that you can’t see is very complex, so we have to constantly keep doing our research, and finding the balance between drilling for geothermal fluid and reinjecting it back into the reservoir. The EIB is helping us ensure a sustainable use of the resource here at Hellisheidi,” Marta explains.

“Climate change affects us all in so many ways. The best thing we can do here in Iceland is help minimise greenhouse gas emissions and share our expertise to help the world shift from fossil fuels towards renewables. Green energy is the only way forward.”

Though more than 10% of Iceland is still covered by glaciers, ice is melting fast. “People remember the size of glaciers from their childhood and today they are visibly much smaller,” Marta Rós explains